New Open Access Book – Controlling the Capital

While many consider authoritarianism on the national scale, ‘Controlling the Capital: Political Dominance in the Urbanizing World’ trains its gaze

How politics and power shape state capacity

Why do certain parts of the state in Africa work so effectively despite operating in difficult governance contexts? How do

New Open Access Book – Political Settlements and Development: Theory, Evidence, Implications

Based upon a decade of ground-breaking research within the Effective States and Inclusive Development (ESID) research centre, Political Settlements and

New Open Access Book: The Politics of Distributing Social Transfers: State Capacity and Political Contestation in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia

Social protection has risen to a prominent position on the global development agenda since the turn of the millennium. Considerable

Open access books make OUP’s top 10 titles

We're thrilled that two of ESID's recent open access publications have made the Oxford University Press' top 10 economics books

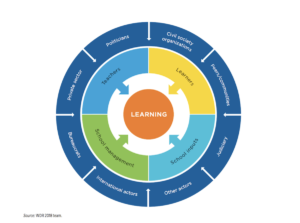

How can civil society help improve learning outcomes?

Professor Brian Levy Following our first blog on the politics of learning reforms, this article focuses on how different stakeholders

The politics of learning reforms: how can governments be held to account?

In the first of two blogs, we outline the findings from ESID's research on the polities of learning reforms The

How women matter in making change

To mark International Women's Day, Professor Sohela Nazneen presents the key findings of ESID's work on women's empowerment. You need

WEBINAR – The politics of building state capacity in Africa: What role for ‘pockets of effectiveness’?

Dr Marja Hinfelaar, SAIPAR Associate Professor Abdul-Gafaru Abdulai, University of Ghana Dr Badru Bukenya, Makerere University Chair: Professor Sam Hickey,

Why should I care about economic growth?

Director of UNU-WIDER, Professor Kunal Sen is a world-leading expert in development economics and led on ESID's research into economic

Alesha Porisky

Role Alesha is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Toronto, an incoming professor

WEBINAR – The politics of addressing Africa’s urban challenge

Dr Eyob Gebremariam, London School of Economics Dr Tom Goodfellow, University of Sheffield Professor Diana Mitlin, Global Development Institute Chair:

WEBINAR – The politics of managing Covid-19 in China and India: A comparison

Prerna Singh, Mahatma Gandhi Associate Professor of Political Science & International Studies at Brown University, USA Professor Yanzhong Huang, Director,

WEBINAR – The politics of learning reforms: How can governments be held to account?

Developing countries have been more successful at widening access to education than raising learning outcomes, partly because it is harder

WEBINAR with Sohela Nazneen – Gatekeepers and gamechangers: How do women matter in making change?

Using case studies from research conducted in Nepal, Bangladesh and Uganda, this webinar reveals how powerful women are critical actors

WEBINAR with Professor Dan Slater – Clustering development and democratisation in Asia

Rethinking Asian geography involves making the case for 'developmental Asia' as a region transcending the conventional divide between Northeast and

WEBINAR – Power, populations and development: How the ESID political settlements database explains development trends

12 November 2020 Recent ESID work has refined the idea of a political settlement and strengthened its social scientific footing.

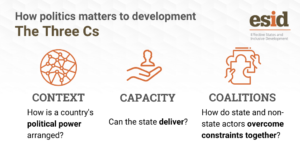

WATCH – Webinar with Prof Sam Hickey: How politics shapes development: The importance of context, capacity and coalitions

9 November 2020 What kind of politics help to secure inclusive development? After nine years of research across 26 countries, summing

New ESID Webinar Series

13 October 2020 We’re excited to announce a new ESID webinar series synthesising more than 9 years of research. Next

Zambia’s response to Covid-19 Part 3: Rising infections and falling confidence amidst increased authoritarianism

Our ESID Zambia experts reveal the latest developments in the political response to Covid-19 in Zambia In a provocative piece in

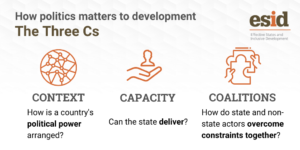

The Three Cs of inclusive development: Context, capacity and coalitions

30 September 2020 Sam Hickey and Tim Kelsall set out the ESID framework for inclusive development. When ESID started its

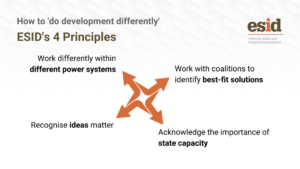

How to work politically for inclusive development: Four principles for action

Sam Hickey and Tim Kelsall What kinds of politics can help to secure inclusive development, and how can these be