Researching the politics of development

Blog

How to work politically for inclusive development: Four principles for action

What kinds of politics can help to secure inclusive development, and how can these be promoted?

These were our guiding questions throughout almost a decade of DFID-funded research, spanning 26 countries, involving over 80 international researchers, focusing on exactly what our name suggests – Effective States and Inclusive Development: how can countries excel while leaving no people or groups behind?

Distilling such a wealth of information was never going to be easy, but we’re keen that these insights are made as accessible as possible.

Our Three Cs of inclusive development are a way to navigate the most significant of our findings – since the themes of Context, Capacity, Coalitions kept coming up as key drivers of development everywhere we conducted research.

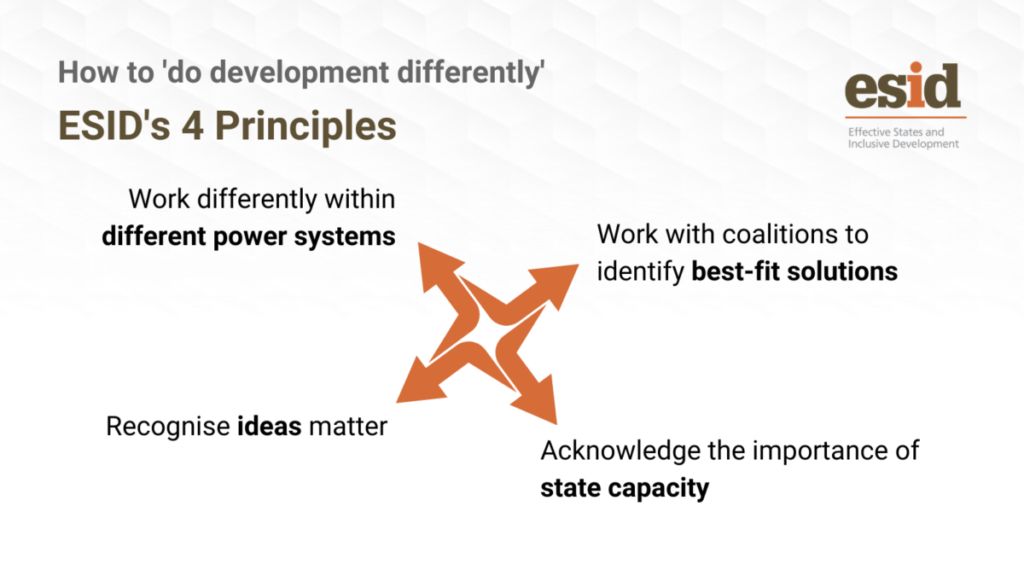

We also wanted to share what we think should be done differently in development, in light of what we now know. To that end, we’ve developed our Four Principles for Inclusive Development – outlined below.

We believe following these principles will help those involved in development to think through who to work with and how best to work with them to achieve more inclusive, sustainable positive change.

Some of these principles may feel instinctive to the experienced development practitioner, particularly those who have already engaged with the now well-established movement towards ‘thinking and working politically’. But our work provides an evidence base and rationale for why these instincts are well-founded, and can help provide a guide to action.

One: Move from avoiding politics → Working differently within different power systems

Like it or not, development work is inherently political. That’s not to say we advocate international agencies taking a political stance; more that national and local politics needs to be seriously and systematically assessed to understand how it could influence the route taken and the outcomes achieved.

The focus of our work has been to understand how power is arranged, in what are termed ‘political settlements’, and to work with that understanding.

When we look at how power operates, we see that different countries achieve inclusive development through very different means.

Take maternal health, for example. Rwanda’s dominant political settlement has provided the context for strong, top-down governance of the health sector. This helped the country achieve the MDG5 target of reducing maternal mortality by more than 75 percent.

Bangladesh, meanwhile, has a more competitive political settlement, and suffers from weak state capacity. Yet here, non-state, private and some public actors have been able to drive improvements in family planning and private healthcare. These improvements have helped the country almost meet MDG5. Both countries developed, but through very different routes.

Understanding how power is distributed in a country and working with that knowledge is essential to finding the best routes to social reform.

Two: Move from imposing best practice → Working with coalitions to identify best-fit solutions

How can countries develop in a way that leaves no people or groups behind?

It would be convenient if there were a single formula for inclusive development. Attempts to establish a ‘best practice’ for development may stem from noble intentions for fairness and expediency in improving life for people globally. But given differing histories, cultures, structures, power dynamics and ideas in different contexts, ‘best practice’ begins to look flimsy when it overlaid on reality.

And yet, we can’t treat every context with such specificity that any attempt at action gets stymied.

At ESID, our approach has been to find a happy medium between ‘blanket’ and ‘bespoke’. We know contexts differ, but we find they differ in similar ways, depending primarily on the nature of their political settlements – in other words, the rules of the political and economic game. Political settlements analysis forms the bedrock of our work and, we think, offers a way in to a more ‘best-fit’ approach to development.

In our research, we frequently found that coalitions of key actors (including politicians, bureaucrats, development partners and civil society players) were able to navigate the choppy waters of a given political settlement and generate workable solutions that fitted the context. Rather than arriving with preconceived solutions, working with and/or helping to build coalitions that have interests in and ideas around core development problems is likely to be a better first step.

All of this means finding ways to approach an issue in a way that takes into account political context, state capacity, and the role of coalitions in tackling barriers to development. It means asking not ‘what works best?’ but ‘what will work best given this particular set of circumstances?’

Three: Move from assuming decisions are based on incentives → Recognising ideas matter

A key part of recognising that ‘politics matters’ is accounting for the role of prevailing ideas in a particular context. Ideas matter – ideas on nationhood, on who belongs and who doesn’t, on redistribution, the relationship between state and capital, and so on.

Ideas also matter at the level of solutions: governing elites often only buy into external policy ideas on things like domestic violence or cash transfers when they solve a pressing political problem, an existential crisis, or they fit their ideological frame.

Take the decision by governing elites to invest in large-scale cash transfer programmes in several African countries that we studied, such as Ethiopia, Rwanda and Mozambique, for example. This rested on a perception amongst elites that cash transfers were a policy instrument that could help address their vulnerability to social unrest.

Working with this knowledge is a matter of taking opportunities that present themselves and framing issues wisely for the local situation. Efforts to advance policies around women’s empowerment show this in action. In Uganda, Bangladesh and Ghana, the language of ‘women’s rights’ was dropped to avoid a direct confrontation with paradigmatic ideas about gender relations. Instead, women’s activists reframed the case for anti-domestic violence legislation in terms of ‘family values’ and ‘development’. Working with dominant ideas helped move the dial, whereas confronting them head-on would have held things up.

Such an approach also requires caution, however. It can lead to the downplaying of more contentious issues, in this case around the co-ownership of resources and marital rape. It remains unclear as to whether the gains made through such compromises will place a ceiling on women’s rights or open the door to further, more progressive gains over time.

Four: Move from fixating on good governance → Acknowledging the importance of state capacity

Formal international consensus has, until relatively recently, focused on promoting institutions of ‘good governance’. That has typically meant working from the belief that the further countries travel towards developing liberal institutions – involving free market economies, rules-based governance and democratic competition for power – the greater their chances of achieving economic growth and human development.

The kinds of external reforms that flowed from this approach tended to run aground once they encountered the political realities of most developing countries, largely because of the ways that political settlements operate in such contexts.

As with the earlier effort to promote economic liberalisation, promoting open and competitive forms of politics before strong institutions have been built proved to be a recipe for chaos and capture. As one formulation puts it, before states can be held accountable, they first need to be capable of developing and delivering policies in the first place.

The success of developmental states in East Asia reminds us that developing countries do not necessarily need to achieve effective and inclusive modes of governance across the board in order to deliver progress.

State capacity is often concentrated within ‘pockets of bureaucratic effectiveness’ with commitment and capacity to deliver on key objectives.

Our research in five African countries identified such pockets within finance ministries, central banks and revenue authorities, and the critical role that they have played in delivering macroeconomic stability, economic growth and increased revenue mobilisation.

We found that political elites are more likely to offer sustained support to high-performing bureaucratic organisations in concentrated settlements with longer time-horizons. Where dominant rulers also perceived that certain social groups within the settlement posed a threat to its stability, this support could spill over into a wider project of state-building.

Importantly, the fact that most such pockets are involved in sustaining neoliberal policy agendas reflects an ideological bias within international assistance. This has left states in Africa poorly equipped to deal with key contemporary challenges such as structural transformation.

Building the capacity, as well as the accountability, of states in Africa to deliver broad-based development will require a much more balanced approach.

If you found these principles useful, why not share them? If you’re Tweeting, use #EffectiveStates and #InclusiveDevelopment, and mention @GlobalDevInst