Researching the politics of development

Blog

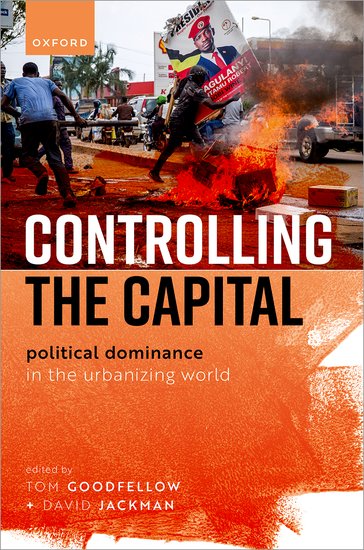

New Open Access Book – Controlling the Capital

While many consider authoritarianism on the national scale, ‘Controlling the Capital: Political Dominance in the Urbanizing World’ trains its gaze on capital cities as spaces in which authoritarian dominance is increasingly built, contested, maintained, and undone.

The open access book, edited by Tom Goodfellow and David Jackman and published by Oxford University Press brings together the research undertaken as part of a project entitled ‘Cities and Dominance: Urban strategies for political settlement maintenance and change’, funded by the Effective States and Inclusive Development Research Centre.

Focusing on some of the world’s fastest urbanizing regions – Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia – the book explores the multiple ways in which authoritarian regimes have been attempting to build and sustain long-term dominance in capital cities in order to meet the challenge of urban political resistance.

With chapters on Addis Ababa, Colombo, Dhaka, Harare, Kampala, and Lusaka, Controlling the Capital offers the first cross-regional comparative study of the relationship between cities and political dominance. It contributes to debates on authoritarianism and authoritarian durability, urbanization, political contestation and resistance, the politics of development, and the prospects for democracy.

Read an extract from Tom and David’s introduction:

The fact that urbanization, authoritarian tendencies, and vigorous political protest are accelerating simultaneously in many parts of the world should perhaps not surprise us. Despite many reasons to believe that urbanization and democracy ought to be mutually reinforcing, existing research on the relationship between the two is very limited, and the evidence is contested. The very same factors that help explain the democratic tendencies associated with cities—namely, population density and diversity, heightened potential for collective action, and generally higher levels of education—often also produce efforts to dominate cities through authoritarian practices.

It is thus far from clear that urbanization produces democracy in the short to medium term, even if it tends to over the longue durée. Meanwhile, in much of the world urbanization is being accompanied by a range of authoritarian strategies on the part of leaders seeking to stave off the threat of democracy.

This tension between the urban democratic impulse and the authoritarian urge to control cities from the top down dates back millennia. What is different in the twenty-first century is the sheer scale of cities, the pace of their growth in many parts of the world, and the breaking of the link between mass urbanization and the generation of urban economic opportunities. In this context, the clash between democratic and authoritarian impulses in cities often leads to an escalation of urban political violence.

It has been argued that, globally, violence has become markedly more urban, and we have turned from the ‘peasant wars of the 20th century ’to the ‘urban wars’ and ‘slum wars’ of the twenty-first. As one commentator puts it, ‘urban areas have become lightning conductors for our planet’s political violence’.

In the context of rapid demographic changes, major cities have emerged as key sites within which struggles over the legitimacy and survival of regimes are played out, and opposition movements seek to gain support and influence. All of this has also become increasingly visible, as social media and other platforms enable efficient and ubiquitous coverage of events, demonstrations, and reprisals, often in highly public and symbolic spaces, such as large squares and junctions. Meanwhile, recent literature has critiqued linear ideas of ‘urbanization of violence’, arguing that it is more helpful to see heightened political violence and protest in cities as mutually entangled with violence at different scales and geographies.

The centrality of cities in both producing and resisting authoritarianism raises critical questions for the study of authoritarian politics. Recent decades have seen the emergence of a rich literature attempting to explain the nature of transitions to authoritarianism, the institutional heterogeneity such regimes exhibit, and their varying durability. With a few exceptions, however, non-democratic regimes and practices have been analysed at the national scale, with little attention to the key roles played by particular subnational places.

What political role do cities—and, in particular, capital cities—play in contemporary authoritarian contexts? Answers to such a question are surprisingly difficult to find, yet in some respects feel obvious. Images of the urban protest inspired by the Arab Spring around the world, or similarly of democracy movements in Hong Kong or Caracas, highlight the campaigns of brutal repression unleashed on cities. Scenes of armed and uniformed security agencies heavy-handedly repressing citizens on city streets are unfortunately too commonplace, but also risk leaving a simplistic impression about both urban politics and the ways that political regimes to seek and establish dominance.

If we move beyond headline-grabbing scenes of open urban protest and repression, it is clear that in many cities the work of establishing political dominance over cities happens behind the scenes or in ways that stifle or coopt dissent before it becomes visible. As well as asking how urban protests emerge and how they are responded to, we need to consider a range of other questions if we are to understand the nexus between urban opposition and urban control. How do some authoritarian regimes prevent urban protests from happening in the first place? What levers of power do they command beyond coercion? What role do forms of longer-term repression and manipulation of opposition forces play? How do some regimes manage to co-opt substantial proportions of the urban population—or even convince them of their legitimacy—even as their authoritarian practices increase?

This book addresses these questions, and in so doing hopes to open up a more complex story about how authoritarian regimes seek and sustain power, and the place of cities within these processes in the early twenty-first century.