Researching the politics of development

Blog

Political settlements in post-conflict states: David Craig's lessons from Cambodia and the Pacific

23 May 2014

By Kate Pruce.

Current donor approaches to ‘successful transition’ in post-conflict states focus on institutional reforms, with the aim of creating an underlying settlement leading to strengthened security and democracy. However, this narrative simplicity disappears in any attempt to map this kind of sequence to a particular case. David Craig, Associate Professor at the University of Otago, and Doug Porter, Adjunct Professor at the Australian National University, have conducted political and institutional analyses of the contrasting cases of Cambodia and the Solomon Islands to explore the dynamics of post-conflict arrangements in reality. They engage closely with ESID’s language, which contributes to the framing of the current debates on political settlements.

Craig acknowledges that political settlement is a contested term, observing that the concept is foundational but operationalisation is messy. This echoes some of the questions raised during the recent ESID mid-term research workshop about the usefulness of political settlements as a conceptual tool – is it even measurable? – and whether the variety of different approaches within the ESID projects may necessitate a greater flexibility in the political settlements framework.

The seminar also highlighted that there are different possible uses of analysis that have differing implications: a normative approach aims to produce best practice based on ideas of how things should be and can be used instrumentally, for example to secure funding; a critical analysis emphasises the role of power, looking at the drivers of outcomes; a positive approach deals with empirics – what is actually there, what are the mechanisms?

ESID’s research programme combines all three types of analysis in its aim to determine ‘What kind of politics can help secure inclusive development, and how can these be promoted?’ using ‘an ‘adapted political settlements’ approach that draws in important insights from the broader realms of political theory, and particularly from more critical approaches’.

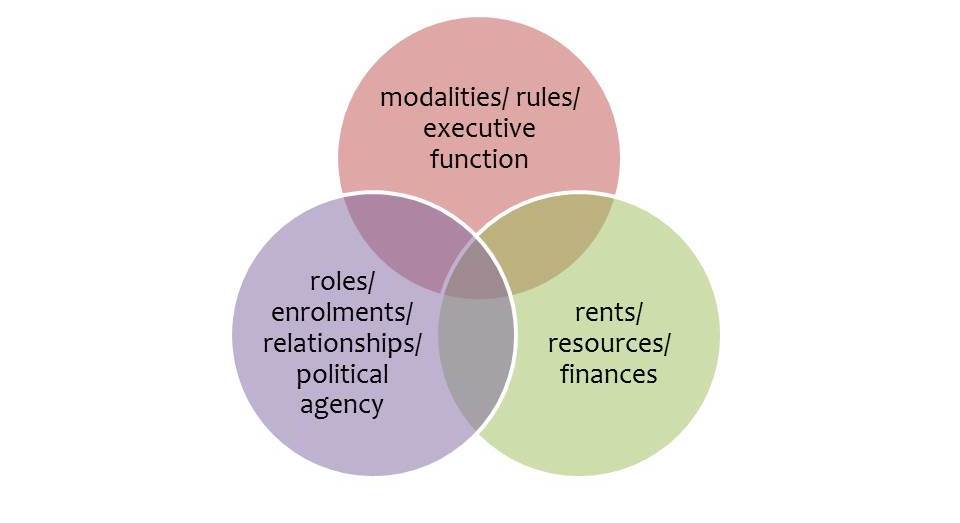

Building on Khan’s definition of ‘political settlement’ as “a combination of power and institutions that is mutually compatible and also sustainable in terms of economic and political viability” (2010: 4), Slater’s identification of two forms of pact and two different pathways – ‘protection’ and ‘provisioning’ (2010), and Hickey’s critical work on political settlement and open access orders (2013), Craig and Porter have developed a model for mid-level political-institutional capabilities analysis. The model has three overlapping areas reflecting basic structuration: rules, roles and rents. They argue that capabilities and accountabilities are created at the nexus between these three areas and that these can be informal as well as formal.

The Cambodia case study is a 25-year retrospective of a local development programme called ‘SEILA’, which aims to achieve ‘poverty reduction and environmental protection through good governance’. The modalities of the programme were translated into the Cambodian context, then co-opted, adapted and imitated by enrolled political actors trying to settle politics. The actors involved were often ‘multi-hat wearing’ (local/international) and despite attempts to coordinate, other programmes emerged creating institutional layering issues.

Travelling from Cambodia to the Solomon Islands, we find that this country is ‘not your typical state’: it is a highly segmentary society with significant ethnic tensions. The Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands (RAMSI) intervention, funded mainly through bilateral aid from Australia, aimed to address these tensions and improve the way the government works, but has encountered three mid-level logics of post-conflict institutional capability.

The first is geopolitics and the primacy of provisioning. ‘Provisioning pacts’ tend to be short term in order to form a government and are therefore easily weakened, due to lack of elite enrolment and unsustainable spending through the sharing of rents. The second is ethnic cleavages and the transactionalisation of pacts, in which pact formation is monetised by elites trying to consolidate their own positions and seek enrolment across ethnic divides. Finally co-production and layering lead to the channelling of resources into modalities where they can be used to enrol political support, for example the Constituency Development Funds.

Craig and Porter found that strengthening of formal structures can occur alongside a simultaneous increase of the informal sector and a weakening of political accountability. Institutional outcomes are not set in stone by political economy. Rather, outcomes emerge, intended and unintended, over time, and in a range of temporal relations that can reinforce or corrode capabilities. Layering can and does produce surprising results over time: fragmentation, but also hybridity and places for ‘multi-hat wearers’ and political actors to hide, adapt, learn, reform.

These conclusions are highly relevant for donors, who are becoming increasingly aware of the importance of political economy within international development assistance. The experiences of Cambodia and the Solomon Islands contradict existing neat donor narratives regarding post-conflict transition. In fact they raise challenging issues about the limitations of aid modalities and the possibility of positive versions of elite capture to create stable politics – not an easy sell, as ‘good governance’ rhetoric still echoes in the corridors of aid agencies.

This post is based on a lecture by David Craig held on 14 May 2014 at The University of Manchester as part of the development@manchester seminar series, supported by ESID, IDPM and HCRI.

For further information view:

Full powerpoint presentation from the lecture.

David Craig’s profile at the University of Otago.

Doug Porter’s profile at the Australian National University.

References:

Hickey, S. (2013). ‘Thinking about the politics of inclusive development: towards a relational approach’. ESID Working Paper No. 1. The University of Manchester.

Khan, M. (2010). Political Settlements and the Governance of Growth-Enhancing Institutions. <http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/9968/1/Political_Settlements_internet.pdf>

Slater, D. (2010). Ordering Power: Contentious Politics and Authoritarian Leviathans in South East Asia.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.