Researching the politics of development

Blog

Kenya's response to Covid-19

29 April 2020

Matthew Tyce

Along with several other African countries, Kenya has so far opted against a full Covid-19 lockdown. The government reacted to its first confirmed case on 13 March by banning public gatherings, then added school closures and flight bans shortly after. On 25 March, with 25 confirmed cases, Kenya imposed a dusk-to-dawn curfew. Additional restrictions came on 6 April, with partial lockdowns of four counties with the highest infection rates – Nairobi, Mombasa, Kilifi and Kwale.

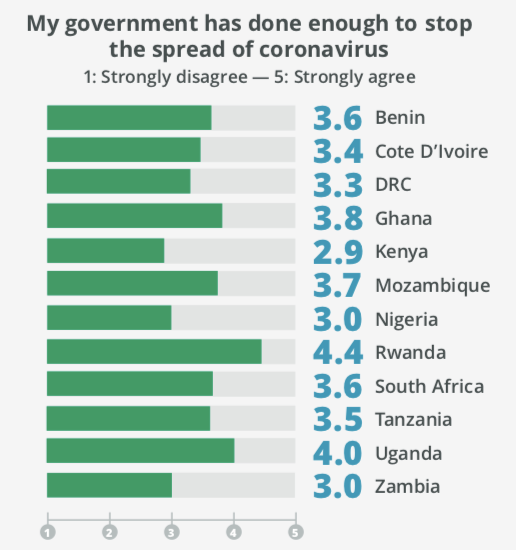

According to the Daily Nation, these staggered measures have slowed the spread of the virus, while striking a difficult balance between protecting lives and livelihoods. Yet the sentiments of the population are seemingly not so positive, as a poll conducted in 12 African countries suggested that Kenyans were the least effusive about their government’s response to Covid-19. Source: GeoPoll.

Source: GeoPoll.

There are perceptions that Kenyan politicians have not been directing all of their energies towards the pandemic, prompting growing accusations of ineffective leadership (Kenya’s omnipresent health minister, Mutahi Kagwe, aside). There is talk of President Kenyatta’s ‘triple headache’, whereby the president has not been fully focused on protecting lives and livelihoods because he is also preoccupied with Kenya’s succession politics ahead of the 2022 elections. Instead of ‘plac[ing] toxic politics into suspension’, to ensure that all the state’s ‘energies and resources were directed into the war against the virus’, Kenyatta has joined other leaders around the world in using the crisis to bolster his position and marginalise opponents. His allies have been given ‘presidential blessings‘ to flout travel restrictions and attend meetings with allies of Raila Odinga, Kenyatta’s ‘post-handshake’ partner, on “’succession issues’ and how to undermine Deputy President Ruto’s presidency bid.

The continued political manoeuvrings and general non-compliance of elites, combined with the violence that is inflicted on citizens by police before their curfew has even started, will only exacerbate a pre-existing lack of trust in Kenya’s political leadership and erode the social capital that is required to combat Covid-19.

Source:The Standard.

Other aspects of Kenya’s response have been tinged by political opportunism. On 25 March, Kenyatta unveiled tax measures to ease financial burdens on Kenyans, including income tax relief for lower earners, corporate and VAT tax cuts and a reduced turnover tax for MSMEs. Broadly, these measures were well received, albeit with caveats that they would benefit the small proportion of Kenya’s population that pays taxes and do little for the vast informal and agricultural sectors that Kenyan policymakers and others across Africa have long ‘ignored’.

However, by the time Kenya’s draft Tax Laws (Amendment) Bill was tabled in parliament, it had become ‘a 97-page tome of deletion after deletion and insert after insert‘, leading to accusations of measures being introduced by ‘stealth’. Professor Attiya Waris, a fiscal policy expert at the University of Nairobi, identified various proposed measures that seemed to represent ‘opportunistic funding of lobby groups … and the loudest voices in government and those connected to them’. These criticisms, inside and outside of parliament, led to some measures being dropped, notably increased taxes on certain staple food items. However, others remained, including tax exemptions on helicopters that politicians are so fond of using. Forthcoming ESID research shows that intra-elite deal-making around tax policies and exemptions has been a long-standing phenomenon in Kenya, linked to its political settlement.

So, too, will upcoming ESID research examine the challenges that Kenya’s National Treasury faces around budgeting, which have been apparent in its response to Covid-19. To offset revenue losses, and re-direct funds towards coronavirus mitigation, the Treasury tabled a supplementary budget. Within it, Ksh10 billion was slated for distribution to the elderly and vulnerable through Kenya’s relatively well-developed cash transfer system, while a new budget line for Covid-19 response was allocated Ksh3.9 billion. In total, the Treasury says it allocated Ksh40.3 billion for pandemic-related expenditures. However, some analysts have described this as little more than ‘tinkering‘ within a Sh1.93 trillion budget. The Health Ministry’s (overall reduced) allocation was criticised as being particularly ‘inadequate’.

According to the renowned Kenyan economist, David Ndii, the Treasury’s ability to fund a more significant fiscal intervention has been constrained by the fact that ‘Kenya’s budget deficit is already well below the redline’. Years of escalating borrowing and politicised spending have eroded the ‘fiscal space’ that allowed Kenya to launch a sizeable stimulus package after the 2007/08 global financial crisis. The Treasury is ‘walking a fiscal tightrope‘.

However, the Treasury did still manage to find space to significantly increase the budget of the Office of the President, with the bulk accounted for by funding for the newly-created Nairobi Metropolitan Service, which Kenyatta is using to ‘gut devolution‘ by taking key powers from Nairobi City County Government and concentrating them within his office. Kenya’s Parliamentary Budget Office has warned that a significant proportion of these allocations may not be pandemic-related and were made ‘contrary to PFM regulations‘. Additionally, the Treasury has allocated Ksh71 million to the Office of the former Prime Minister, controlled by Kenyatta’s newfound ally Raila Odinga, while reducing funding for the Deputy President’s office. Again, this has given many Kenyans the sense that their leaders are more interested in fighting ‘succession wars‘ than the coronavirus.

Yet there have also been many silver linings in Kenya’s response. Its Central Bank, recognised in ESID research as a ‘pocket of effectiveness’, has been praised for its response to the crisis, particularly by quickly imposing a moratorium on mobile money fees to aid the flow of remittances and reduce cash circulation that was soon copied elsewhere. To mitigate its own fiscal restrictions, the Treasury has encouraged a variety of public and private actors to donate to the Covid-19 response fund. Questions have been raised about the transparency of the fund, but it has raised billions of additional shillings by tapping innovative sources of finance, including ‘dirty money‘ recovered from Kenya’s recent anti-corruption drive.

Answering President Kenyatta’s calls for Kenyans to channel their innovative spirit towards combatting the coronavirus, Kenya’s tech community has also developed software to aid laboratory testing and a digital dashboard to monitor supplies, allowing existing HIV testing infrastructure to increase capacity to a point where it can ‘test upwards of 37,000 coronavirus samples in 12 hours‘. Sub-nationally, county governments such as Kitui and Mombasa have worked with garment manufacturers to re-orient production towards PPE equipment like face masks, while the national government has assisted by suspending restrictions on firms within Export Processing Zones, where most manufacturers are located, from selling domestically.

All these examples affirm ESID’s broader findings that, while so-called ‘dispersed’ political settlements like Kenya’s might undermine the coherency and capacity of the central state to respond to crises like Covid-19, they do also leave room open for – and are often more permissive of – collaborative, multi-stakeholder initiatives that can creatively fill those gaps.