Researching the politics of development

Blog

Do Gram Panchayat leaders favour their own constituencies in MNREGA fund allocation?

By Dr Subhasish Dey and Prof Kunal Sen

By Dr Subhasish Dey and Prof Kunal Sen

3 January 2017*

Political incentives are known to play a role in the allocation of public resources from upper- to lower-tier governments. This column seeks to examine whether ruling parties in local governments favour their own constituencies in allocating MNREGA funds, whether they target their core supporters or swing voters, and whether this has any electoral returns. It is based on ESID Working Paper 63, ‘Is partisan alignment electorally rewarding? Evidence from village council elections in India‘, also by Dey and Sen.

An influential literature has highlighted the role of political incentives in the allocation of public resources from upper- to lower-tier governments (Dixit and Londregan 1996, Dahlberg and Johansson 2002). So far, the empirical evidence on the role of political incentives has mostly focused on intergovernmental transfers or grants, and there is limited evidence on whether partisan alignment is also evident for other public programmes, and how lower-tier governments allocate funds once they are received (Dasgupta et al. 2004).

Village councils (or Gram Panchayats, GPs), which are the lowest level of government in India, administer several social welfare programmes for the poor. Among the most important, in terms of both total funds allocated through GPs and households covered, is the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA),1 which is India’s largest anti-poverty programme.2 GPs play a central role in registering households for the scheme, selecting the projects that should be funded by the scheme, as well as undertaking the projects with the help of local bureaucrats and MNREGA project staff once funds reach the village.

Do political incentives influence the allocation of funds by local politicians to their constituencies? Do they favour certain wards in their constituencies and, if so, do they target their core supporters or swing voters? And are there electoral rewards in targeting certain types of voters?

To address these questions, we examine whether ruling parties in local governments (GPs) in the state of West Bengal favoured their own constituencies in allocating funds for MNREGA and in providing MNREGA work to households residing in the constituency, and whether this had any electoral returns (Dey and Sen 2016). We used a rich primary dataset from 569 villages (or village council wards) over 49 GPs from three districts of West Bengal for 2010-2012.3 Local government elections took place in 2008 and 2013, allowing us to see whether there was a targeting of specific constituencies after the 2008 elections and whether this had any electoral pay-off in the 2013 elections. During 2008-2013, there were two principal contesting parties in West Bengal with dissimilar political ideologies: a coalition of leftist parties – the Left Front (LF) – led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI(M)), and the Trinamool Congress (TMC). The fact that there were two political parties in different parts of the state running the GPs allowed us to see whether there was any difference in the behaviour of these two parties in the manner in which they targeted certain constituencies, and whether this led to differences in electoral rewards for the two political parties.

To understand whether political incentives mattered in the allocation of MNREGA funds by local politicians, we faced two empirical challenges. Firstly, if we see a positive association between the allocation of public funds to a constituency or better MNREGA implementation and whether the constituency is under the control of the incumbent party, it could be due to the party’s innate preference to favour certain constituencies, rather than a deliberate strategy to win votes. Secondly, a similar challenge exists in establishing that the targeting of MNREGA funds to certain constituencies implied that voters in these constituencies rewarded the incumbent party with greater support in the next elections. Voters may prefer a particular party or candidate for reasons other than how well the MNREGA was implemented in the constituency.

To address the first challenge, we looked at the constituencies where politicians of the ruling party marginally won elections at the village level versus the constituencies where they marginally lost. Since constituencies where the ruling party marginally won elections should be no different than the constituencies where they marginally lost, comparing the constituencies in this way allowed us to see whether MNREGA allocation of funds or its implementation in constituencies where the ruling party marginally won differed significantly from the cases where the ruling party marginally lost constituencies. If we did find that there was a significant difference, we could attribute this to the targeting of the winning constituency by the ruling party. To address the second challenge, we looked at the effect of increased MNREGA funds and implementation that could be reliably attributed to targeting of marginal constituencies by the ruling party on electoral returns of the incumbent party.

We find clear evidence that after the 2008 Panchayat elections, the ruling party at the GP level significantly spent more MNREGA funds in all the following years in their own party constituencies as compared to the constituencies of their opponents. Our estimates suggest that a village which is a ruling party’s winning village receives Rs. 38,750 more in terms of MNREGA expenditure compared to a non-ruling party’s village, and that households in the ruling party’s winning village receive 3.59 days more of MNREGA work compared with the households in the non-ruling party’s village.

Targeting swing voters vs. core supporters

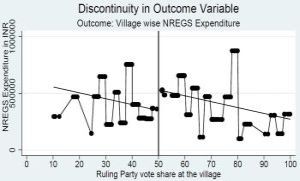

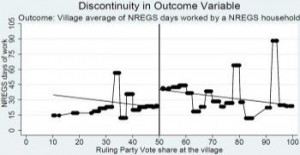

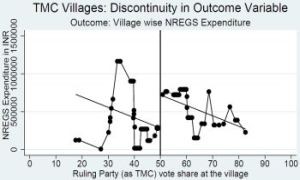

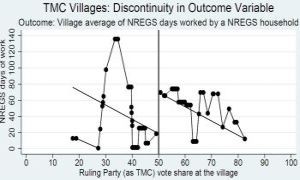

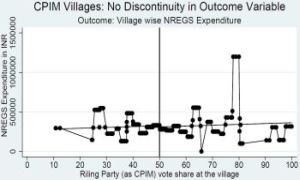

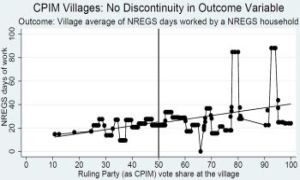

In Figure 1, we see a sharp jump in MNREGA allocation of funds to constituencies and days worked where the ruling party marginally won at just over 50 percent of the votes, versus constituencies where they marginally lost to the opponent party. This suggests that the ruling party in West Bengal targeted swing constituencies instead of the constituencies where they had core support (that is, constituencies where they had the majority of votes). However, we find that the targeting of marginal constituencies differed between the two main political parties – while TMC-run GPs targeted marginal constituencies, CPIM-run GPs did not. As is clear from Figure 2, there was a significant difference in MNREGA fund allocation and implementation between the constituencies. TMC marginally won versus the ones they marginally lost. But we find no such difference in MNREGA allocation of funds or implementation between marginal constituencies won by the CPIM and the marginal constituencies that they lost (Figure 3).

What explains the difference in behaviour between the two political parties? We conjecture that the differences in behaviour between the two political parties can be attributed to the anticipation of regime change in the state as the TMC was making strong inroads in the GPs formerly held by the CPI(M), which provided little incentive for the CPI(M) to engage in targeting swing constituencies, as well as the class background of the potential beneficiaries of the MNREGA, who were agricultural labourers that have historically not been the core supporters of the left regime in West Bengal.

Figure 1. Effect of any party being GP-level ruling party on village-level MNREGA outcomes

Figure 2. Effect of TMC being GP-level ruling party on village-level MNREGA outcomes

Figure 3. Effect of CPI(M) being GP-level ruling party on village-level MNREGA outcomes

Electoral returns

Were there any electoral returns to the TMC for engaging in such partisan behaviour? We find strong electoral returns to such behaviour – GPs ruled by TMC after 2008 Panchayat elections managed to secure a higher percentage of votes as well as a higher probability of re-election in their own constituencies in the following 2013 Panchayat elections, while such an outcome was not observed for CPI(M)-run GPs. The TMC, as a ruling party after 2008 elections at the GP level, realised a 1.5 percent increase in their vote share in their own villages in the 2013 elections by spending an extra Rs. 100,000 MNREGA funds annually in their own constituencies compared to opponent party constituency. In contrast, the CPI(M) as the ruling party in the 2008 elections realised a fall in their vote share in their own constituencies in the 2013 elections, as they did not engage in such partisan behaviour.

Policy implications

Our findings suggest that whether MNREGA worked well or not in a particular village in West Bengal depended to a large extent on whether TMC saw a clear electoral return in targeting the village. This shows that to understand why social welfare programmes work well or not in the Indian context, more attention needs to be paid to the incentives of political parties to implement them well. Moreover, the decentralised nature of implementation of MNREGA may have worked to its disadvantage in West Bengal, in cases where the GP leaders were not motivated to implement MNREGA well. This implies that there may be a trade-off between the objectives of empowering GPs and of providing social protection to the poor, which was not fully realised by the advocates of MNREGA, who wanted the scheme to be primarily implemented by local governments rather than by state and central governments.

This article was originally published at ideasforindia.in.

Notes

- The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA), 2006 guarantees 100 days of employment in a financial year to every rural household whose adult members are willing to do unskilled manual work at the minimum wage.

- In the state of West Bengal, about 80-90 percent of the total funds received by GPs from upper-tier governments is for the MNREGA.

- The data has been collected by Subhasish Dey.

Further reading

- Dahlberg, Matz and Eva Johansson (2002), ‘On the vote-purchasing behaviour of incumbent governments’, American Political Science Review, 96:27–47.

- Dasgupta, Sugato, Amrita Dhillon and Bhaskar Dutta (2004), ‘Electoral goals and centre-state transfers in India’, University of Warwick Working Paper. Available here.

- Dey, Subhasish and Kunal Sen (2016), ‘Is partisan alignment electorally rewarding? Evidence from village council elections in India’, Effective States and Inclusive Development (ESID) Working Paper No. 63.

- Dixit, Avinash and John Londregan (1996), ‘The determinants of success of special interests in redistributive politics’, The Journal of Politics, 58(4): 1132–1155.