Researching the politics of development

Blog

The social protection agenda within Zambia’s distributional regime

By Kate Pruce

By Kate Pruce

8 February 2017

Although Zambia was reclassified by the World Bank as a middle-income country in 2011, poverty levels remain high, with 54.4% of the population living below the poverty line and over 40% in extreme poverty in 2015. The increased per capita gross national income (GNI) is not benefiting everyone, and inequality as measured by the Gini index has risen from 50.8 in 2004 to 57.5 in 2013, making Zambia one of the world’s most unequal countries.

Cash transfers are currently receiving a lot of attention as an instrument for tackling poverty and vulnerability. Not all of this coverage is good – a recent Daily Mail article painted a picture of UK taxpayer money being given away to citizens in Pakistan, describing it as ‘exporting the dole’. However, there is a growing body of evidence that cash transfers have a range of positive developmental impacts, including reduced monetary poverty, increased school attendance and increased uptake of health services, while recent FAO evaluations counteract a number of common myths about cash transfers.

Building an evidence base for social cash transfers has been a key element of the politically-informed strategy adopted for promoting social protection in Zambia. Impact evaluations of the Multiple Categorical Targeting Grant (MCTG) and the Child Grant (CG) models have demonstrated many promising findings. These results include reductions in extreme poverty and the poverty gap, improved food security and a multiplier effect through productive impacts. These studies have been particularly persuasive among Ministers – “they certainly like evidence, Ministers love it, they’re all doctors, so they love Randomised Control Trials” (interview with cooperating partner). However, technical evidence is not the only factor in determining whether a social protection programme is adopted and expanded by a government.

“They certainly like evidence, Ministers love it, they’re all doctors, so they love RCTs”

This paper, co-authored with Sam Hickey, is part of a wider ESID project comparing the politics of social protection in five African countries: Ethiopia, Rwanda, Kenya, Uganda and Zambia. Papers by Tom Lavers and Benjamin Chemouni on Ethiopia and Rwanda argue that in both these countries social protection is driven by a particular developmental vision and is also needed to build legitimacy of the dominant coalition governments. In the other case studies, however, social protection initiatives have been donor-led, often trying to overcome resistance from a ruling coalition with short-term political interests based on maintaining a competitive settlement. In these countries, the formation of a transnationalised policy coalition in favour of social protection has been a critical aspect of the story to date.

“The formation of a transnationalised policy coalition in favour of social protection within Zambia has been a critical aspect of the story to date”

While evidence has been used to good effect in Zambia to convince powerful players within government about the merits of social protection, progress remained limited until there was a shift in political settlement dynamics which led social protection to become more aligned with the interests and ideas of a new ruling coalition. In 2013, a 700% increase in the government funding for Zambia’s social cash transfer (SCT) came out of the blue to the policy coalition. This boost took place under the Patriotic Front government, which took power in 2011 on a pro-poor ticket, including a manifesto commitment to rolling out social transfers. Following a scandal in 2013 concerning massive overspend on agricultural subsidies, then-President Michael Sata redirected funds to SCTs. The pro-poor messaging of the Patriotic Front has provided some space for the social protection agenda to gain ground. However, doubts about whether commitment is genuine suggest that this may have been used to legitimise a decision that was actually triggered by the agricultural subsidy crisis.

“The SCT programme was framed as a more effective and pro-poor alternative to the subsidies… it could be seen as the solution because the scheme had already been accepted by the finance ministry as a credible means of reaching the poor, and because a degree of capacity existed within government to deliver”

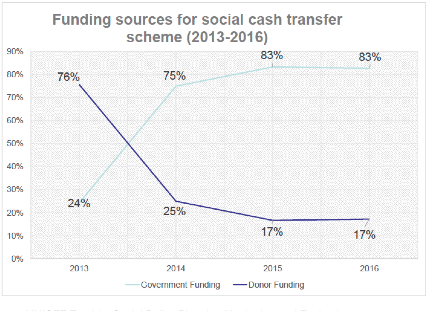

A capable and committed SCT team within the Ministry of Community Development managed, under political pressure, to rapidly scale up the programme, which doubled in size to reach almost half of the districts in Zambia by the end of 2014. The budget increase also reversed the balance of donor and government funding (see Figure 1), thereby reducing reliance on external funding.

Figure 1: Funding sources for social cash transfer scheme (2013-2016)

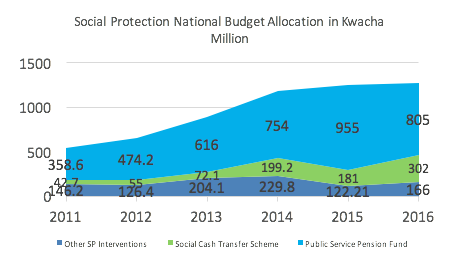

Figure 2: Social protection national budget allocation in kwacha (million)

The paper contrasts this progress on the SCT agenda with social health insurance, another area of Zambia’s National Social Protection Policy that has received significant attention but has made little headway. The ‘coalition’ around SHI has been more fragmented, with little involvement from larger donors and senior political figures, and a lack of an evidence-based plan for how this complex scheme would work in practice.

In the wider ESID project, the aspect of ideational fit has emerged as being significant for the uptake of social protection policies. One of the reasons social protection has yet to become more fully established in Zambia may flow from the sense in which the discourse on social protection has not tapped into the deeper paradigmatic ideas that underpin the political settlement in Zambia, nor seriously challenged existing ideas about dependency and deservingness. There is also little demand for social protection from voters, with both government officials and recipients seeming to perceive SCTs as being a gift rather than a right. This suggests that the conditions do not currently exist for social protection to be institutionalised as part of a new social contract in Zambia.

“The conditions do not currently exist for social protection to be institutionalised as part of a new social contract in Zambia.”

Nonetheless, the SCT budget has been increased again in 2017 and – at a time of economy-wide crisis – social protection forms the second pillar in Zambia’s Economic Recovery Plan (ERP) to ‘cushion the poor’ from the effects of planned austerity measures. There is a sense within the policy coalition that this current political and fiscal space needs to be seized to consolidate the programme and scale-up further. The plan is to reach nationwide coverage by the end of 2017, an achievement which is so far unusual for a donor-driven pilot scheme, leading a key informant in the Ministry of Community Development to suggest that the scheme has reached a point of ‘political irreversibility’.

Given that it would be politically challenging to remove SCTs at this stage, what matters now is the way in which these transfers become integrated within Zambia’s distributional regime in the context of high levels of poverty and inequality.

For more on this topic, read Working Paper 75, ‘The politics of promoting social protection in Zambia‘.