Researching the politics of development

Blog

Building effective states beyond competitive democracy in Ghana

By Dr Daniel Appiah and Dr Abdul-Gafaru Abdulai

By Dr Daniel Appiah and Dr Abdul-Gafaru Abdulai

18 April 2017

It is widely accepted that the creation of impartial organisations is an important condition for spurring economic growth and development on a sustained basis. Democracy requires impartial enforcement of rules that promote liberty, equality, property rights and open competition for public office. Both procedural and substantive definitions of democracy therefore include a system of rule of law enabled by impartial bureaucratic organisations.

Public sector reforms to remove patron-client organisations from Africa’s expanded public bureaucracies have been strongly supported by international development agencies. However, there is some emerging consensus that it takes a long time to establish impartial bureaucratic organisations. A longstanding question of scholarly interest is whether competitive democracies in developing countries can sustain public sector reforms aimed at establishing the impartial organisations required for stimulating economic growth and development.

Since Ghana returned to multi-party democratic politics in 1992, political power has been alternating between two political parties, the National Democratic Congress (NDC) and the New Patriotic Party (NPP). Electoral competition between these parties has become increasingly intense. Each party has lost power after eight years of rule, and power has alternated between them, following elections in 2000, 2008 and 2016. Thus, Ghana is among the few countries in Africa that have surpassed Samuel Huntington’s ‘two-turnover’ test of democratic consolidation.

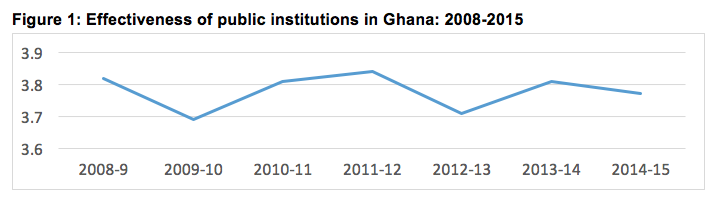

However, the Ghanaian experience shows that not all good things necessarily go together: while competitive elections for executive recruitment have deepened to the level found in advanced democracies like the USA and UK, the effectiveness of the country’s public institutions has declined, in spite of numerous reforms sponsored by the Bretton Woods institutions and other international development agencies (see Figure 1 below).

Source: World Economic Forum – Global Competitiveness Index, 2005-2015 (performance is measured on a 7-point scale where 1 is worst and 7 is best).

But what is more puzzling in our research analysis is the finding that, although public sector reforms in the area of public financial management (particularly in auditing and procurement) have largely enjoyed continuity since the late 1990s, every government used the reforms to reproduce patron-client organisations that have continued to undermine impartial distribution of public resources, transparency and accountability. There has been little commitment across governments to create impartial organisations for auditing, procurement and anti-corruption. This is in spite of the fact that international development agencies demonstrated continuing interest in public financial management reforms by providing financial and technical support.

Our findings support the conclusion that, while frequent change of democratically elected governments in Ghana undermines reform continuity and success, continuity of reforms does not guarantee reform success in the establishment of Weberian social norms and impartial organisations. We argue that debates about how to build impartial state organisations should go beyond the current focus on the nature of reform sequencing. Reform projects in developing countries characterised by intense electoral competition should seriously consider, first, how to create a coalition for reform across existing competitive political groups and, second, how to mobilise political elites and the voting citizens to support the establishment of the impartial organisations required for sustainable socio-economic development and democracy.

This post is based on Working Paper 82, ‘Competitive clientelism and the politics of core public sector reform in Ghana‘.