Researching the politics of development

Blog

Has Chhattisgarh done better than Jharkhand in promoting inclusive development? A political settlements analysis of two newly created mineral rich Indian states

Vasudha Chhotray

9 September 2016

Leading academics and policy experts recently met at the Centre for Policy Research in India to discuss the findings of our latest research on new Indian states. Here, lead researcher Dr Vasudha Chhotray outlines the key findings..

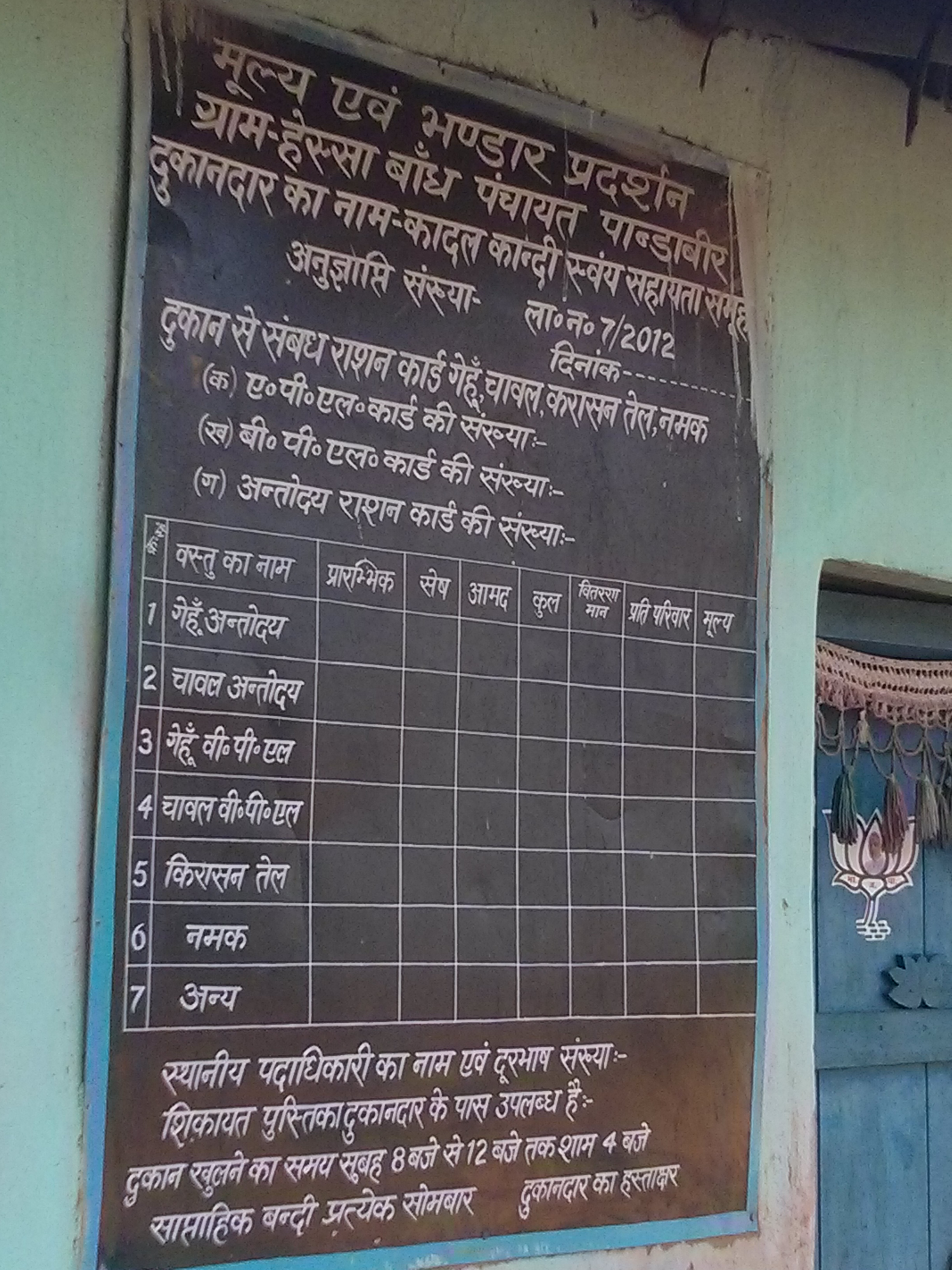

Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand are two mineral rich states in central and eastern India, created in November 2000. Starting out with some broad similarities – significant Adivasi populations, large forested areas, and mineral wealth – the two states have embarked upon quite distinctive trajectories of growth, poverty reduction and social welfare programmatic outcomes, with Chhattisgarh leading in important respects. Chhattisgarh has aggressively pursued industrial investment, promoted an ambitious agenda of power generation and reformed the Public Distribution System (PDS) to deliver subsidised food grains to majority poor households.

Both states have pursued mining activities as a part of a broader emphasis on modernisation based on mega industries and development. However, while mining is important for economic growth, it comes with large-scale questions of dispossession, environmental transformations with unfair burdens for the poor, and acts of resistance, as seen in both states. So how the two newly created states compare, not only in terms of facilitating mining, but also in dealing with the social costs of mining, either through direct investments from mining royalties or through other welfare agendas, is an extremely relevant question.

While there is abundant research on the PDS in both states, especially Chhattisgarh, and on mining, no other study has tackled these two in relation to one other. By juxtaposing the politics of extraction with the politics of social welfare provisioning, this study sets out to examine the extent to which inclusive development has been promoted in each state.

In order to compare the trajectories of development, this research adopts a political settlements approach, which characterises the political arrangements between the various socio-economic groups in society, i.e. between political, economic and other social elites, and between elites and a range of subordinate groups, which are stable at a point in time, and influence the distribution of benefits by the existing institutions. It also considers which ideas or cognitive maps become influential within the political settlement, and the role they might assume in driving outcomes.

Over two years, researchers carried out more than 200 key informant interviews at the respective state capitals and four purposively selected district headquarters, plus case study work with interviews, group discussions and field observation at the block and village level, involving one public and one private sector mining actor in each state. Project partners also carried out an analysis of fiscal policies for the two states.

Adopting a political settlements approach has allowed us to go beyond conventional explanations centring on the type of regime or political agency or institutional functioning that has dominated scholarship so far. Chhattisgarh’s political settlement is marked by relatively higher levels of elite cohesion in political competition, greater bureaucratic autonomy enabled by better organised and more centralised rent-seeking, more explicit state capitalism, and harsh crackdowns on networks of non-violent civil society and violent Maoist resistance. In contrast, Jharkhand’s political settlement has lower elite cohesion in political competition, low bureaucratic autonomy produced by multiple decentralised transactions for rent-seeking, weak state capitalism and stronger networks of peaceful civil society resistance as well as more dispersed acts of violent resistance.

Research findings strongly suggest that differences in outcomes and trends in development between the two states, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand, depend on their respective political sett lements. Being multi-dimensional, the political settlements approach lends itself to a more nuanced and multifaceted assessment of their respective performance in moving towards inclusive development. We can conclude that the political settlement in Chhattisgarh has certainly enabled the promotion of service delivery and, to an extent, facilitated mining better than that of Jharkhand.

lements. Being multi-dimensional, the political settlements approach lends itself to a more nuanced and multifaceted assessment of their respective performance in moving towards inclusive development. We can conclude that the political settlement in Chhattisgarh has certainly enabled the promotion of service delivery and, to an extent, facilitated mining better than that of Jharkhand.

Jharkhand’s PDS system is both inefficient and corrupt, its mining sector is ridden with delays and hurdles, but equally, those protesting in favour of the rights of local communities are not as easily dismissed. At the same time, the continuation of high levels of corruption in Chhattisgarh (both in mining and within the PDS system through expanded rice procurement) and brutal dealings with protestors raises serious questions around transparency, accountability and political inclusion.

Chhattisgarh’s superior functioning PDS is a vital constituent in the ruling coalition’s bid for legitimacy and management of social costs, given the wider accumulations and dispossessions underway. The same is not possible within Jharkhand’s political settlement, where the broken nature of the welfare system leaves the ruling elites relatively more exposed to criticism for all-round mismanagement. This suggests that we cannot conclude that Chhattisgarh has necessarily done better than Jharkhand in promoting inclusive development, or that it should indeed be regarded as an exemplar amongst low-income states in India.

These lessons are pertinent for those who advocate smaller new states for ostensibly reducing spatial inequality and promoting the positive politics of recognition of historically disadvantaged communities. This research shows that whether this happens in practice, as in the case of Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh, would depend on the political settlement around elite bargaining, cognitive maps that elites hold, historically acquired state capacity and state treatment of protest.

Read about this research in ESID briefing 18.