Researching the politics of development

Blog

Zambia’s response to Covid-19 Part 2: 'We have to choose life or livelihood or both'

30 May 2020

Discover the latest on the response to Covid-19 in Zambia

Any glimmer of hope that the Covid-19 crisis would provide an opportunity for technocrats to assert themselves, within the increasingly personalised approach to policy-making under Zambia’s ruling Patriotic Front (PF) party, seems to have disappeared. Since our previous blog, President Edgar Lungu has made several controversial moves that suggest the health advisors have already been sidelined.

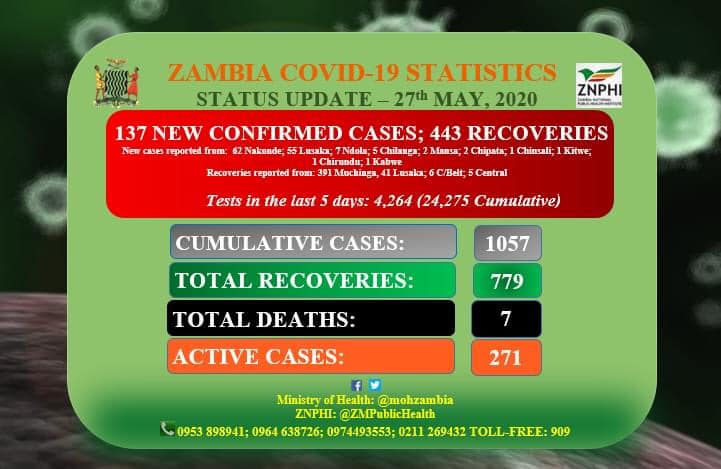

As the total number of confirmed cases in Zambia passes the 1,000 mark, the Ministry of Health continues to deliver daily Covid-19 updates and press briefings. However, these are becoming increasingly politicised, with some within PF considering the Health Minister, Dr Chitalu Chilufya, to be a potential threat, and this is undermining the level of trust in the information being conveyed. Chilufya has also clashed with Minister of Finance, Dr Bwalya Ng’andu, who is speaking out publicly about Zambia’s unsustainable debt and budget financing gap, as well as demanding greater accountability of Zambia’s COVID-19-related funds.

In the early stages of Covid-19 in Zambia, a coalition of Ministry of Health officials and health partners, including the World Health Organisation (WHO) and Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), appeared to be at the forefront of the response. The key role of such national-level coalitions, bringing together political leaders and technical experts, within a political settlements analysis, provided some hope that the technocrats would be given more space. However, while the Ministry of Health in particular has largely retained control of the flow of public information, the influence of the coalition over government directives is more limited.

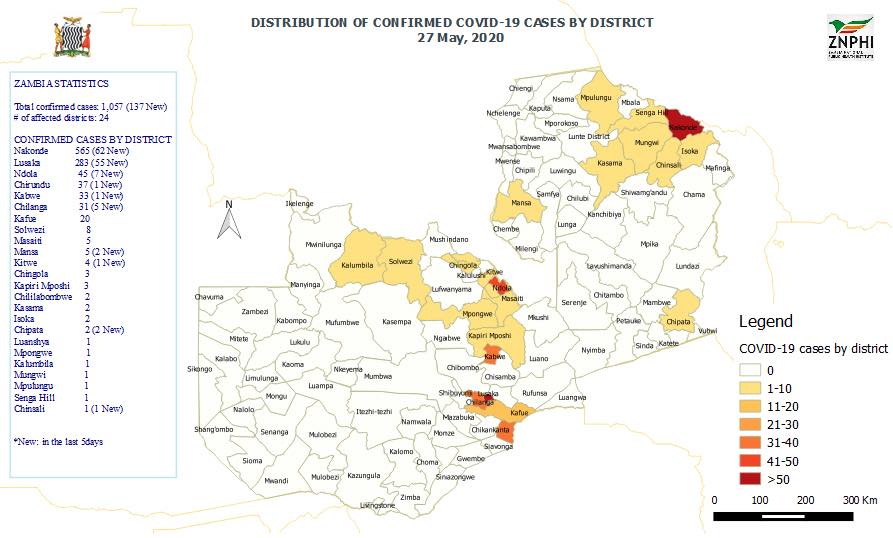

For example, the current strategy of closing hotspots, such as the town of Nakonde on the border with Tanzania, is in line with the recent WHO advice for Africa. However, the medical experts in Zambia called for a complete lockdown of points of entry as early as January, but the government did not listen to this advice. The call to close the Nakonde border was made two weeks before the localised outbreak occurred, but was ignored. The temporary closure of the border was finally ordered just before a spike of 208 new cases in the area, concentrated among truck drivers, was announced within a 24-hour period. Lungu has since publicly directed the Minister of Health to handle the Nakonde situation in a way that allows business to keep flowing, despite more than half of Zambia’s Covid-19 cases (565) being located in this area.

The significant increase in Zambia’s total number of cases came days after the president’s fourth national address on Covid-19 on 8 May, in which he announced the re-opening of restaurants, cinemas, gyms, tour operators and casinos, among others, although bars must remain closed. Critics have suggested that this selective re-opening is favouring specific businesses because they are owned by people within government, and indeed many of them are not important sectors within Zambia’s economy. As early as 24 April, President Lungu decided to allow some activities to resume, including congregating at places of worship, seemingly under pressure from the Ministry of Religious Affairs and National Guidance, as well as individual religious leaders. He also announced that barbershops and salons could re-open, despite the inherent difficulties of social distancing in such settings, presumably appealing to ‘that barber in Chiwempala, and that young lady who plaites hair in Mazabuka‘ who have been losing income due to the restrictions.

This move towards a ‘new normal’ through the easing of some restrictions reflects the delicate balance that all countries are seeking between reviving the economy and avoiding a public health crisis. Lungu claims that it might be possible to achieve the best of both worlds – ‘We have to choose life or livelihood or both’ – while apparently prioritising economic and political interests, despite a rapid rise in the number of cases and projections that the Covid-19 peak in Zambia will be in two or three months.

However, some of these presidential directives are being resisted. The statement that places of worship could re-open caused division among churches, as many told their members not to congregate. State House defended the announcement, by saying that this was not a directive, but advice for churches to make their own decision. But, as lodge owners and tour operators contest the order to resume their operations, the tone has become increasingly authoritative, with President Lungu giving a warning not to argue or politicise his directive. Lungu is also turning to religion by directing the nation, through its Ministry of Religious Affairs, to observe seven days of National Prayer and Fasting, entitled ‘Help from Above in the face of Covid 19’.

In the face of this rapid rise of cases and corresponding government measures, the public is divided. Some are worried and think the government should be doing more. According to a study conducted in 12 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Zambia and Mozambique have the highest perceived risk of catching the virus, at 82 percent and 83 percent, respectively. Zambia also had among the highest portion of respondents who strongly disagreed that their government was doing enough (31 percent). On the other hand, others are resisting the measures that are being put in place, as demonstrated by the riot in Nakonde in response to the lockdown.

Zambia’s response to Covid-19 is limited by underlying economic and structural constraints. Financial challenges include low economic growth rates (2 percent in 2019), depreciation of the local currency and unsustainable debt – with central government debt standing at 91.6 percent of GDP at the end of 2019 (IMF, 2019). Limited state capacity and long-term under-investment in healthcare also undermine the response and have recently come under heavy criticism, in the wake of a road traffic accident that killed a young lab technician carrying Covid-19 test samples. This incident highlights both inadequate health systems – with only three testing centre in the whole country – as well as poor road infrastructure and safety, particularly in terms of public transport. Dr Chilufya explained that the technician used public transport because the Ministry vehicles were being used for other purposes, which led to a public outcry about the use of funds donated for the Covid-19 response and a challenge from Lungu, who demanded an investigation.

In terms of mitigating the impact of Covid-19 on the economy, the government has released K2.5 billion and Zambia has also received contributions from a wide range of donors, totalling K3.5 billion (about GBP 157 million). However, there are strings attached to these donor funds, which have been clearly earmarked for specific purposes. The UK, Sweden and Germany, for example, have all focused on social protection, in particular cash transfers for the most vulnerable. Donors are wary following recent government scandals and are demanding high levels of accountability. They also took this opportunity to urge the government to make the most of this new multilateral emergency support, as well as the recent G20 initiative on debt relief to address Zambia’s longer-term debt crisis. Such requests may help to build Ng’andu’s case for tackling Zambia’s intractable debt issues, in order to be able to engage with the IMF, as he is currently not receiving the support he needs from within government.

While Zambia’s Ministry of Finance has the reputation of being a high performer or ‘pocket of effectiveness’, and is relatively well disciplined, well equipped and resourced, it nonetheless remains highly dependent on the character of the president and ruling coalition. Zambia’s shift from one-party state to multiparty democracy in 1991 did little to change the nature of the executive powers, which have remained significantly concentrated within the top political leadership, specifically the president and State House. Zambia’s political settlement is becoming increasingly authoritarian in character, and the current regime’s profligacy had created significant financial challenges even before Covid-19 struck. Despite protracted talks with the IMF since 2016, Zambia has failed to secure a deal, largely due to the government’s reluctance to demonstrate commitment to fiscal management and resistance to the external accountability that such a programme would entail. In the context of Covid-19, Zambia does not qualify for the IMF’s Catastrophic Containment and Relief Trust and is struggling to access their emergency funding, due to its unsustainable debt levels.

While a broad, relatively concentrated settlement might be expected to have comparatively capable health and social protection sectors, these systems are weak in Zambia, with funds for social sectors squeezed by high debt servicing costs and public wage bill. A more collaborative strategy is therefore needed, integrating non-state actors, particularly development partners and NGOs, in order to tackle the health and economic effects of the virus. However, recent events suggest that Zambia is moving further down the path of repression and politicisation of the response, and the coalition of health experts initially driving the response is being increasingly sidelined. It is hoped that Zambia’s broad-based civil society and opposition parties can continue to act as a countervailing power as the Covid-19 situation evolves in an increasingly politicised direction.

Read Part 1 on the response to Covid-19 in Zambia.